If never HIGHLIGHTED, many would not be aware of such rights violations, which can amount to 'sexual harassment' too, that is happening in some places in Malaysia. If a girl/women says that she is having her period - then TRUST HER - respect her. The proceeding with physical bodily tests, or the need to show proof, is just not acceptable

'...showing their blood-soaked sanitary pads, doing swabs of their vagina with either cotton buds, tissues, or their fingers, or having a teacher, warden or school prefect pat them down at the groin to feel if they are wearing a sanitary pad...'STOP THESE UNJUST PRACTICE IMMEDIATELY

NEXT, we need to consider WORKERS - WOMEN WORKERS.

Women have to go through menstruation every month. We acknowledge for some when their period comes, they suffer more than others - severe menstrual cramps making it most difficult to work. Many may be forced to utilize the paid annual leaves and/or their paid sick leave - but maybe, it is time to introduce as a right - paid menstrual leave.

The Malaysian government/s can start now - and for the rest, there needs a law to make it a Legal Entitlement - annual paid maternity leave for women - they call this 'MENSTRUAL LEAVE' - and it already exists in some countries.

Menstrual leave is a type of leave where a woman may have the option to take paid or unpaid leave from her employment if she is menstruating and is unable to go to work because of this.

'...Japan's period leave entitlement has existed for more than 70 years, and the country isn't alone in Asia in having such a policy. South Korea adopted period leave in 1953. And in China and India, provinces and companies are increasingly adopting menstruation leave policies with a range of entitlements....' - CNN, 21/11/2020

When '...a short video clip surfaced in November 2005 of a nude woman doing the ketuk ketampi (nude squats) in a police lock-up...' surfaced, this led to public outcry - and now the government has enacted laws that says how any body searches ought to be done.

In 2010,'...in Sivarasa vs Badan Peguam Malaysia & Anor (2010), the

Federal Court stated that the right to personal liberty, as enshrined in

Article 5(1) of the Federal Constitution, includes the right to

privacy. The right of privacy has three dimensions — the right to be

left alone; the right to exercise control over one’s personal

information; and, the right to have a set of conditions necessary to

protect one’s individual dignity and autonomy...To look at the law from a different perspective, there are three

kinds of privacy — physical privacy (freedom from unlawful search, use

of our DNA); information privacy (right to protect personal information

such as our age, address, sexual preference); and, freedom from

excessive surveillance....' - NST, 1/3/2019, Urgent Need For A Privacy Act

As it stands today, Malaysia only have a law that protects personal data, i.e. Personal Data Protection Act 2010 - Not enough, we need a PRIVACY ACT - that will protect even our bodies and dignity being violated.

Gender differences need to be recognized, but we also need to acknowledge the differences amongst women - there are those that really suffer serious cramps(or other effects) on the first(or first few days) of period, and others do not.

Be that as it may, there is a need for Menstrual Leave (paid leave) entitlement.

We now have maternity/paternity leave - but all women have menstrual cycles, and some justly need LEAVE, especially when they are really in a condition where they cannot work or it is just too 'torturous' to work

Would such an entitlement be abused? Well '...A Japanese government survey in 2017 found that only 0.9% of female employees claimed period leave...In South Korea, usage is also dropping. In a 2013 survey, 23.6% of South Korean women used the leave. By 2017, that rate had fallen to 19.7%...' (see below for full report)

There is much that need to be reformed - and when people HIGHLIGHT matters, it comes to our attention, and REFORMS can be fought for and implemented.

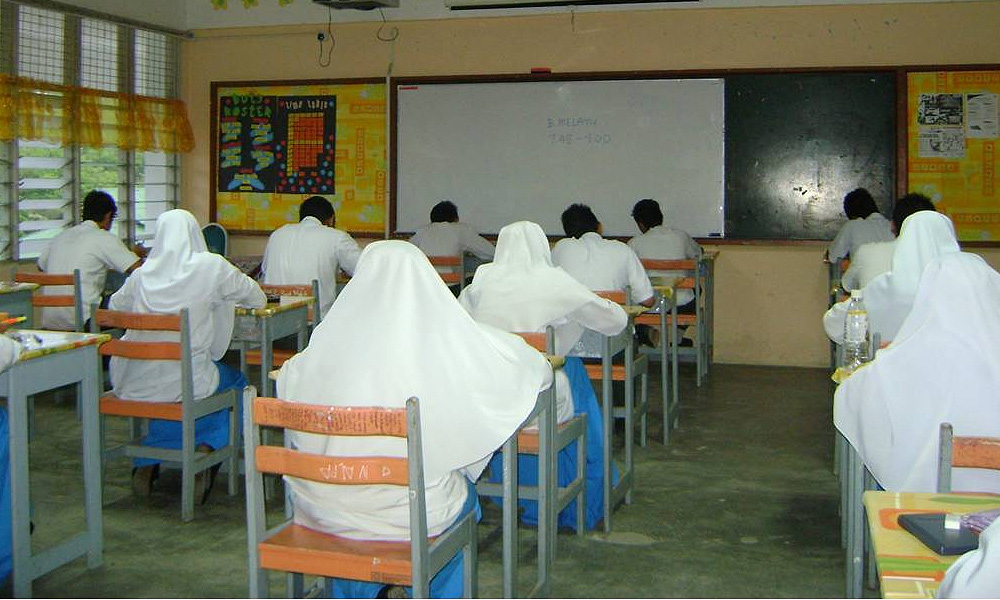

Schoolgirls 'shamed, groped and violated' in period spot checks

Girls in multiple schools in Malaysia have to undergo “period spot checks” where they are told to physically prove they are on their period through means which violate privacy, according to current students and those who left school up to 20 years ago.

The measures include showing their blood-soaked sanitary pads, doing swabs of their vagina with either cotton buds, tissues, or their fingers, or having a teacher, warden or school prefect pat them down at the groin to feel if they are wearing a sanitary pad, they said.

Over a dozen individuals reached out to Malaysiakini in less than 24 hours after a call for stories was made. They recalled how the behaviour towards menstruation at boarding schools was “shameful” but was accepted as “normal practice”.

Many of the girls were from boarding schools but this was also said to be a practice at day schools and Islamic private schools, Malaysiakini was told.

They narrated how their years of growing up from young girls to teenagers, marked by the start of menstruation, became a source of trauma and shame that still haunts them to this day.

A key trigger was the practice of teachers or seniors demanding “proof of menstruation” from girls who did not join daily congregational prayers which are commonly held in residential or religious-based schools.

In Islam, women or girls who are menstruating do not perform ritual prayers.

The ingrained belief that such practices should be accepted often prevented the girls from telling their mothers or guardians, even when feeling violated.

The individuals approached Malaysiakini with their stories, after responding to a question by a Twitter user on whether such practices still exist in school. The Twitter thread sharing these stories has been shared more than 6,000 times.

Those who came forward said they wished to see an end to the harassment and normalised acts of “period shaming”.

They called for more awareness of the rights of students to body autonomy - for them to decide what happens to their bodies without external influence or coercion by not only their peers but also by their teachers and parents.

All names have been changed to protect the identities of those involved.

"We were groped from behind"

Siti N* was a student at a co-ed private Islamic school, an institution comprising both primary and secondary classes.

From Mondays to Thursdays, she said, students were made to join compulsory congregational prayers, while girls on their period would stay in one room where their menstruation cycles were tracked in a record book.

“At times, they would give us a piece of paper or tissue, asking us to go to the toilet and provide a glimpse of our period blood,” she said via WhatsApp.

“I remember at one point, they had asked us to assemble at the football field.

“The teachers and representatives had to check our panties one by one by groping our behind. It was rather demeaning and I felt sick to the stomach,” said Siti who is now in university after completing her secondary education at a different school.

She said she left the school in Form 2, feeling anxious yet relieved to escape the toxic environment and start afresh.

“At the time I thought such acts were something normal for the greater good,” she said, adding that victim-blaming was also a common message indoctrinated in students.

At the age of 13, Adriana* said she entered boarding school with little knowledge of her menstruation cycle and bodily functions, including differentiating between normal vaginal discharge and period blood.

She stayed back in the prep room during the compulsory congregational prayers one night, she said, only to be caught during a “spot check” as having no sign of bleeding.

“The senior in charge thought I was lying and cursed me out of the room, along with other seniors.

“I was traumatised and since then, I will reuse the same pad throughout the day to make sure there will be blood,” she said.

“Looking back, it was so disgusting that I have to use the same pad with blood from the day, just to really prove I am on my period,” said Adriana, now 21.

Vulgar insinuations from teacher

DH* has never opened up about the disturbing incidents during her primary and secondary years at two girls' schools in Kelantan.

To this day, the 35-year-old said her experiences had affected her relationship with her body, from being put off against using a tampon, to overall hesitance to start her own family.

She said congregational Zohor prayers were compulsory for all students in the afternoon session and they would be subjected to random spot checks.

“If it was an ustazah (female teacher) on duty, we would run and hide, or else she will drag us to the toilet and make us ‘swipe our blood’ on tissue.

“If anyone was found to be wearing a tampon, she will shame them, asking ‘are you itching to have a penis in you?’ That comment put me off from using tampons until I was in my 20s,” DH said.

“It wasn’t okay 20 years ago, and it certainly is not okay today in this day and age,” she said, in supporting calls for Sex Education to be taught as a separate subject in Malaysian schools.

Irregular cycles caused suspicion

As recent as five years ago, Ash* said such incidents were a routine occurrence at her government boarding school in a southern peninsula state, with the perpetrators from a “religious squad” targeting groups of girls sitting outside the school’s surau.

“What they would do is they would make us stand in line outside the toilet, taking turns to go in, and one or two squad members would just run their finger through the vaginal area.

“Oftentimes it would just be through the fabric of our skirt, but even then it felt very weird,” she said.

Like the others, Ash said their ignorance led to fear and silence, and she is still seeking mental health treatment for her personal traumas.

“Back then I had very irregular cycles and it caused the squad members to always be suspicious of me.

“Sometimes they would call me out, four or five of them would confront me and they even threatened to make me pull down my underwear entirely,” said Ash, adding that she eventually left the residential school at 16 to enter an ordinary school.

Faekah* was in Form 1 at a boarding school when she was exposed to spot checks and she said that not only was she traumatised but that hygiene was clearly compromised.

“I didn’t know much about my period at that time and if there was vaginal discharge, I would also think it was my period. So one day there was discharge on my panties and because of that, I had to stay in the prep room. But at night, during the spot check, I didn’t have any discharge, and my senior thought I was lying.

“Since that time, if I have the period the whole day, I will still re-use the same pad to pass the spot check at night. But looking back it was so disgusting that I have to use the same pad which had blood from the morning just to please them and to really prove that I was having my period,” she added.

During a menstrual cycle, it is recommended that sanitary pads be changed at regular intervals of not more than three to four hours. Wearing a pad for too long can lead to an infection, including yeast infections, says Healthline.com.

Practice still ongoing

At least two girls who spoke to Malaysiakini under conditions of strict anonymity, as they are still students at the residential schools, confirmed that the “normal practice” is still in place today.

Bee*, who attends Ash’s former school, said the “period swab” to prove inability to perform daily prayers is still being done, and there was an even more disgusting punishment in place targeting girls on their menstruation.

“Many of us, when we were juniors, were made to squeeze our bloodied pads because supposedly we didn’t dispose of it properly.

“That still haunts my mind until now,” she said, adding that many students still remain fearful of speaking out.

Beyond physical harassment, Jana* another current student, also responded with her story of a teacher’s cruel remark, targeting those who avoided the period swab test.

“Those whose periods often did not come must be pregnant,” said a warden at her residential school, according to Jana.

“We were only in Form 1 at the time and her words hurt a lot.”

She said it should be unacceptable for a teacher to make such remarks against a student, particularly at such a young age.

Experts say such tests are invasive, excessive

Penang mufti Wan Salim Wan Mohd Noor told Malaysiakini that no one should embarrass another by checking the private parts of the individual for any reason because everyone has self-dignity that must be respected by others, including the right to cover the private parts of their body from being seen by others.

"Islam strictly forbids its followers from looking at other people's aurat, even on the pretext of performing the required duties such as to prevent a female student from making excuses to abandon the obligation of prayer," Wan Salim told Malaysiakini.

The president of the Association of Islamic Doctors of Malaysia (Perdim), Dr Ahmad Shukri Ismail, also sees the act of checking private parts to prevent students from skipping prayers as excessive.

"It is sufficient with a statement from the individuals involved and there is no need to check the sanitary napkins.

“In Islam, there is no element of coercion. Let's not develop a situation where people see Islam as too rigid," Ahmad said.

Dr Harlina Halizah Siraj, professor of Obstetrics and Gynaecology and Medical Education (Clinical Teaching) with the Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM), said that such actions really encroach on women's privacy and she does not see why it has to be done this way.

"As an obstetrician and gynaecologist, I believe a young woman should not have to prove that she is having her (menses). You should take a woman's word for it," Harlina told Malaysiakini.

Meanwhile, Fadhlina Sidek, head of legal and community development of Wanita PKR, said she objects strongly to period-shaming.

"The act of groping girls to make sure whether they are menstruating or not is sexual harassment, while the act of asking them to show their bloody pads as evidence of menstruation is a crime of bullying, degradation, and disturbs the emotions of girls," Fadhlina said.

Women's groups react

Reacting to the issue, the All Women’s Action Society (Awam), Sisters In Islam (SIS) and Pertubuhan Pembangunan Kendiri Wanita dan Gadis (Women:Girls) demanded that the Education Ministry addresses issues of sexual harassment, body shaming as well as violation of personal autonomy.

"This was done via the excuse of disciplinary punishments but borders on harassment and abuse of power.

"Period spot checks; physically invasive spot checks for ‘forbidden items’; body, clothing and intimate relationship shaming in public; child grooming; molestations; and slapping and pinching of nipples as punishment, are just a few of the violating incidents experienced by students in Malaysian schools that have been brought to the public’s attention recently," said the women's groups in a joint statement.

They said the incidents were reported to have taken place in kindergartens, primary schools, secondary schools, boarding schools and universities.

"This reflects a systemic toxic culture of patriarchy, sexism, harassment, abuse, bullying and religious policing, with our nation’s young people on the receiving end.

"This denotes a chilling prediction for our future adult citizens. Instead of being safe spaces of learning where students can fulfil their greatest potential, our local schools are now sites where:

- Young women are learning to fear, be insecure about and shameful of their clothes and their bodies;

- Adult women not only enduring years of severe mental stress and trauma since their student days but also having this trauma negatively affecting their current relationships, university, and career performance; and

- Young student leaders learning by example about the acceptability of abuse of power and privilege, and are at risk themselves of normalising such behaviour in their own lives."

These are degrading and abusive treatments that violate the physical body and personal boundaries without consent, they said, adding that the abuse is made worse because most survivors are or were underaged when the incidents took place.

They said under the Sexual Offences Against Children Act 2017 and outrage of modesty under Section 354 of the Penal Code, these cases would be considered as criminal offences and are punishable by law.

"By carrying out such actions or allowing such actions to be carried out by teachers/wardens/matrons, our Malaysian school authorities are teaching all students that it is okay to violate another person’s body without their consent and treat them without respect or dignity," said the groups.

Meanwhile, former deputy education minister Teo Nie Ching said it is so far unclear whether there are ministry guidelines that specifically address the methods used to determine whether a girl is having her period or otherwise.

“I cannot recall whether we have anything written to say that a teacher can do so or cannot do so. But I think this is (an issue of) common decency.

“I think once the Education Ministry receives a sufficient number of complaints, of course, it would be better for the ministry to put it in writing, stating what teachers can or cannot do,” Teo, the MP for Kulai, said.

Malaysiakini has also reached out to current Education Minister Radzi Md Jidin for a response. - Malaysiakini, 22/4/2021

Should women be entitled to period leave? These countries think so

Hong Kong (CNN Business)Sachimi Mochizuki has worked in Japan for two decades, but she's never taken a day off for her period.

Widely available, but rarely used

The case for period leave

Why period leave hasn't taken off in the West

No comments:

Post a Comment