Another article written on MERDEKA heroes that appeared in Malaysian Digest on 25/8/2011

The Original Heroes of Merdeka |

| Al-Jafree Md Yusop and Syed Zahar |

| Thursday, 25 August 2011 00:00 |

This article is a tribute to all the forgotten freedom fighters who

fought for Malaya’s independence from the British oppressors,

especially those who were unjustly chastised for their activisms.

How the Fight for Independence Started

How the Fight for Independence Started

Before the Japanese occupation of Malaya and the existence of Umno in

the early 1940s, Ishak Haji Mohammed, popularly known as Pak Sako (left),

risked being prosecuted for treason (punishable by death) by secretly

going to Japan to solicit Japanese help to fight for the independence of

his country. Subsequent to this, Dr Burhanuddin Al-Helmy met with

Soekarno to plan strategies for both countries’ independence. Though the

attempts of both Pak Sako and Dr Burhanuddin failed for various reasons

they were what marked the dawn of Malaya’s fight for independence.

Additionally, it was the independence of Indonesia on August 17, 1945

which was admired by the Malays in Malaya that inspired them to achieve

their own liberation from the British.

Formation of PKMM and Umno

It was not until early 1946 that Malaya’s first independent movement

was initiated in the form of a political party called Parti Kebangsaan

Melayu Malaya (PKMM). Its founding members were Malays of Indonesian

descent, notably Ahmad Boestamam and Musa Ahmad. Whenever and wherever

the party members met, they greeted each other with “Merdeka!” It was

said in a spirited voice with clenched fist brought to the chest. The

party’s first newspaper Suara Rakyat which contents were 100

percent political was published at Hale Street, Ipoh. Before too long,

PKMM opened branches all over the country with its headquarters at Batu

Road (now Jalan Tuanku Abdul Rahman) Kuala Lumpur. It did not take much

convincing or time for Ishak Haji Muhammad (aka Pak Sako) and Dr

Burhanuddin Al-Helmy to join PKMM.

The United Malays National Organisation (Umno) was formed six months after the formation of PKMM. The party was established with the sole objective of opposing the proposed Malayan Union which relegated the powers of the Malayan Rulers to the British Residents. Contrary to popular belief, Umno was not an independence movement. As the leaders of Umno were mostly colonial civil servants who had sold their lives and soul to the colonialists, it vehemently opposed independence. Not only were they anti-independence, the word “Merdeka” was also considered taboo to them. Coincidentally, at that time, Umno’s greeting was “Hidup Melayu!”

Another reason Umno opposed independence was that they felt that the Malays were poor and uneducated and, to them, if the Malays were left to themselves, Malaya would end up being a failed state.

The PKMM, on the other hand, thought otherwise. They wanted to gain independence first and only then would there be ample opportunity to educate the Malays as the country was rich in natural resources, and it would not be a failed state. These opposing stances were what had split the two parties and led to enmity.

The United Malays National Organisation (Umno) was formed six months after the formation of PKMM. The party was established with the sole objective of opposing the proposed Malayan Union which relegated the powers of the Malayan Rulers to the British Residents. Contrary to popular belief, Umno was not an independence movement. As the leaders of Umno were mostly colonial civil servants who had sold their lives and soul to the colonialists, it vehemently opposed independence. Not only were they anti-independence, the word “Merdeka” was also considered taboo to them. Coincidentally, at that time, Umno’s greeting was “Hidup Melayu!”

Another reason Umno opposed independence was that they felt that the Malays were poor and uneducated and, to them, if the Malays were left to themselves, Malaya would end up being a failed state.

The PKMM, on the other hand, thought otherwise. They wanted to gain independence first and only then would there be ample opportunity to educate the Malays as the country was rich in natural resources, and it would not be a failed state. These opposing stances were what had split the two parties and led to enmity.

The Rise of PKMM and the Labour Movement

PKMM became a symbol of solidarity because of its leaders who were

committed to the party’s cause. The party’s spirit, along with their

branches and bureaus grew like wildfire all across Malaya. Apart from

the youth and women’s wings, labour, agriculture and religious bureaus

were established. The labour bureau was the most active and most

successful political agitator. The presence of PKMM was welcomed and

long awaited by the Malayan labour movement and the party’s labour

bureau had no trouble in gaining support from the former seeing as the

labourers’ living conditions at that time were pitiful.

Incidentally, the Malayan labour movement had affiliated itself with the world labour movement, the World Federation of Trade Unions (WFTU), whose headquarters was in Paris, and not with the American-controlled International Labour Organisation (ILO), whose headquarters was in New York. As the French-based WFTU was leftist inclined, the Malayan labour movement’s affiliation to it heightened British suspicion of PKMM.

Between 1946 to1948, the labour movement was so active (except in Kedah, Kelantan and Terengganu) that recurring strikes almost crippled the nation’s rubber and tin industries. The port workers of Singapore also joined in the strikes, incapacitating Malaya’s major port.

Expectedly, the British operative policy of divide and rule was immediately put into action. The British, while pretending to acknowledge the labourers’ plight, declared PKMM as illegal and incarcerated its leaders.

The banning of PKMM only further alleviated the organised strikes and, with that, British economic interests were in jeopardy day by day. The mainstay of the British economy which were the rubber and tin industries, were faced with impending paralysis. With their economic interests threatened, the colonial government sent a loud and clear message to Whitehall to caution them of Malaya’s intention to free itself from the shackles of colonial rule. Whitehall realised soon enough that in the wake of India'and Indonesia attained independence, Malaya’s aspiration could no longer be contained and they had no choice but to grant Malaya its rightful independence sooner or later.

Incidentally, the Malayan labour movement had affiliated itself with the world labour movement, the World Federation of Trade Unions (WFTU), whose headquarters was in Paris, and not with the American-controlled International Labour Organisation (ILO), whose headquarters was in New York. As the French-based WFTU was leftist inclined, the Malayan labour movement’s affiliation to it heightened British suspicion of PKMM.

Between 1946 to1948, the labour movement was so active (except in Kedah, Kelantan and Terengganu) that recurring strikes almost crippled the nation’s rubber and tin industries. The port workers of Singapore also joined in the strikes, incapacitating Malaya’s major port.

Expectedly, the British operative policy of divide and rule was immediately put into action. The British, while pretending to acknowledge the labourers’ plight, declared PKMM as illegal and incarcerated its leaders.

The banning of PKMM only further alleviated the organised strikes and, with that, British economic interests were in jeopardy day by day. The mainstay of the British economy which were the rubber and tin industries, were faced with impending paralysis. With their economic interests threatened, the colonial government sent a loud and clear message to Whitehall to caution them of Malaya’s intention to free itself from the shackles of colonial rule. Whitehall realised soon enough that in the wake of India'and Indonesia attained independence, Malaya’s aspiration could no longer be contained and they had no choice but to grant Malaya its rightful independence sooner or later.

The British Chooses Umno to Negotiate Independence

The British had learnt that independence achieved through war was not

the way to go as this would result in the loss of life and property,and,

more essentially, leaves a grudge within the beneficiary state. In

turn, the outcome would be the less-than-desirable nationalisation of

the colonialists’ assets. Since the British realised that they could

lose everything they decided to negotiate independence. The only

question was who would be the British protégé so that their assets would

be fully protected while the expatriates could hold on to their jobs a

bit longer.

With PKMM banned and its leaders incarcerated, Umno was the safest bet as the latter was the only organised movement that dominated the political scene then. Umno, of course, was very receptive to the British as most of their leaders were British educated and had embraced British culture and values ever since their school days in Britain or at the Malay College Kuala Kangsar (MCKK). Additionally, they were mostly the sons of the Malay rulers and chieftains who had been close to the British. These people had been moulded to become anglophiles who regards the British as their icons and mentors and viewed them as their saviour.

Umno quickly seized the opportunity provided by the colonialists and took over where the PKMM had left off. From an anti-Malayan Union organisation, it suddenly assumed the role of a force fighting for independence. The British were very comfortable with Umno’s new role, and negotiations for independence took off.

The negotiations that followed were mainly technical and focussed on two major issues: to prepare the country’s constitution and to agree on the date of the declaration of independence. A body was formed, headed by Lord Reid, to look into a constitution and the date of independence was agreed as August 31, 1957. For political exigency, Umno would have to forge an alliance with the ethnic Chinese and Indian political parties, and hence “Perikatan” (Alliance) was formed.

Pending full independence, Malaya was ruled by the Federal Legislative Council consisting of appointed members representing the various races and professions. With independence granted, the British got to retain the entire system and had their assets protected. For Umno and the Alliance, the declaration of independence was a jubilant moment as it was achieved without shedding a drop of blood.

With PKMM banned and its leaders incarcerated, Umno was the safest bet as the latter was the only organised movement that dominated the political scene then. Umno, of course, was very receptive to the British as most of their leaders were British educated and had embraced British culture and values ever since their school days in Britain or at the Malay College Kuala Kangsar (MCKK). Additionally, they were mostly the sons of the Malay rulers and chieftains who had been close to the British. These people had been moulded to become anglophiles who regards the British as their icons and mentors and viewed them as their saviour.

Umno quickly seized the opportunity provided by the colonialists and took over where the PKMM had left off. From an anti-Malayan Union organisation, it suddenly assumed the role of a force fighting for independence. The British were very comfortable with Umno’s new role, and negotiations for independence took off.

The negotiations that followed were mainly technical and focussed on two major issues: to prepare the country’s constitution and to agree on the date of the declaration of independence. A body was formed, headed by Lord Reid, to look into a constitution and the date of independence was agreed as August 31, 1957. For political exigency, Umno would have to forge an alliance with the ethnic Chinese and Indian political parties, and hence “Perikatan” (Alliance) was formed.

Pending full independence, Malaya was ruled by the Federal Legislative Council consisting of appointed members representing the various races and professions. With independence granted, the British got to retain the entire system and had their assets protected. For Umno and the Alliance, the declaration of independence was a jubilant moment as it was achieved without shedding a drop of blood.

The Lowering of Union Jack and Hoisting of Malayan Flag

“On August 31, 1957, Malaya was re-reborn. As the clock struck

midnight, the Union Jack was lowered and the new Malayan flag was

hoisted in front of the clock tower opposite the Selangor Padang. The

shouts of “Merdeka!” – no less than seven times –

reverberated and resounded in the air. The shouts were led by Tuanku

Abdul Rahman, who stood on a rostrum surrounded by his Cabinet

Ministers, some of whom, I observed, were obviously drunk.” – Dato’ Hishamuddin Yahaya (former MP of Temerloh)

The next morning, the official declaration of independence was held at Stadium Merdeka, attended by all the Malay Rulers, the British High Commissioner and the representatives of the Queen (Duke of Gloucester etc). With that, Malaya established itself as an independent state, a member of the British Commonwealth and member of the United Nations.

Malaysia’s independence was the cumulation of a long and hard struggle, a triumph attained not by the elite class, but by labourers and the downtrodden – who now lay in the graves unknown and forgotten. They were Malays, Indians, Chinese and others who sacrificed their lives and freedom for future generations, yet whose existence we hardly knew. It is these pure nationalists who rightfully deserve to be glorified on August 31 every year and not the so-called patriots who hoisted the Malayan flags at the compound of their mansions and on their luxurious automobiles.

The next morning, the official declaration of independence was held at Stadium Merdeka, attended by all the Malay Rulers, the British High Commissioner and the representatives of the Queen (Duke of Gloucester etc). With that, Malaya established itself as an independent state, a member of the British Commonwealth and member of the United Nations.

Malaysia’s independence was the cumulation of a long and hard struggle, a triumph attained not by the elite class, but by labourers and the downtrodden – who now lay in the graves unknown and forgotten. They were Malays, Indians, Chinese and others who sacrificed their lives and freedom for future generations, yet whose existence we hardly knew. It is these pure nationalists who rightfully deserve to be glorified on August 31 every year and not the so-called patriots who hoisted the Malayan flags at the compound of their mansions and on their luxurious automobiles.

In any case, Winston Churchill’s statement that “History is written by

the victors” is dead on; yet the Latin proverb “Fortune (and history for

that matter) favours the brave” is far from the truth. Perhaps there

is a need for change in what has been written in our history

textbooks...

The Most Notable Unsung Heroes of Merdeka

Ahmad Boestamam (30 November, 1920 – 19 January, 1983)

Ahmad Boestamam (right)

was an activist of the leftist Kesatuan Melayu Muda (KMM) movement.

During the Japanese occupation of Malaya, he had briefly served with the

Japanese sponsored militia known as the Pembela Tanah Ayer (Defender of

the Homeland; PETA) and later helped to organize co-operative communes

run by the KMM.

Ahmad Boestamam (right)

was an activist of the leftist Kesatuan Melayu Muda (KMM) movement.

During the Japanese occupation of Malaya, he had briefly served with the

Japanese sponsored militia known as the Pembela Tanah Ayer (Defender of

the Homeland; PETA) and later helped to organize co-operative communes

run by the KMM.

Boestaman had been a young follower of the KMM from the late 1930s in Perak, emerging after the war as the militant youth leader of Angkatan Pemuda Insaf (API) to the older and more moderate Dr Burhanuddin Helmi and Ishak Haji Muhammad of the Malay Nationalist Party (PKMM).

Ahmad Boestamam (right)

was an activist of the leftist Kesatuan Melayu Muda (KMM) movement.

During the Japanese occupation of Malaya, he had briefly served with the

Japanese sponsored militia known as the Pembela Tanah Ayer (Defender of

the Homeland; PETA) and later helped to organize co-operative communes

run by the KMM.

Ahmad Boestamam (right)

was an activist of the leftist Kesatuan Melayu Muda (KMM) movement.

During the Japanese occupation of Malaya, he had briefly served with the

Japanese sponsored militia known as the Pembela Tanah Ayer (Defender of

the Homeland; PETA) and later helped to organize co-operative communes

run by the KMM.Boestaman had been a young follower of the KMM from the late 1930s in Perak, emerging after the war as the militant youth leader of Angkatan Pemuda Insaf (API) to the older and more moderate Dr Burhanuddin Helmi and Ishak Haji Muhammad of the Malay Nationalist Party (PKMM).

Dr Burhanuddin Al-Helmy (26 November, 1911 – 6 November, 1969)

Dr Burhanuddin Al-Helmy (left)

became a Parti Islam Se-Malaya (PAS) member on December 14, 1956 and

became party’s president on December 25, 1956. He was approached by some

PAS leaders like Haji Hassan Adli and others who guaranteed that the

leadership of PAS will be trusted to him. Under the leadership of Dr

Burhanuddin, the popularity of the party became famous and it became

more widely accepted by the Malays. In 1956 and 1959, the seat of

presidency was being contested and Zulkifli whom opposed him in the

presidency post. No doubt that Dr Burhanuddin’s personality, appearance

and attitude had won the hearts of many PAS members and thus elected him

as the new president of PAS.

Dr Burhanuddin Al-Helmy (left)

became a Parti Islam Se-Malaya (PAS) member on December 14, 1956 and

became party’s president on December 25, 1956. He was approached by some

PAS leaders like Haji Hassan Adli and others who guaranteed that the

leadership of PAS will be trusted to him. Under the leadership of Dr

Burhanuddin, the popularity of the party became famous and it became

more widely accepted by the Malays. In 1956 and 1959, the seat of

presidency was being contested and Zulkifli whom opposed him in the

presidency post. No doubt that Dr Burhanuddin’s personality, appearance

and attitude had won the hearts of many PAS members and thus elected him

as the new president of PAS.

Dr Burhanuddin Al-Helmy (left)

became a Parti Islam Se-Malaya (PAS) member on December 14, 1956 and

became party’s president on December 25, 1956. He was approached by some

PAS leaders like Haji Hassan Adli and others who guaranteed that the

leadership of PAS will be trusted to him. Under the leadership of Dr

Burhanuddin, the popularity of the party became famous and it became

more widely accepted by the Malays. In 1956 and 1959, the seat of

presidency was being contested and Zulkifli whom opposed him in the

presidency post. No doubt that Dr Burhanuddin’s personality, appearance

and attitude had won the hearts of many PAS members and thus elected him

as the new president of PAS.

Dr Burhanuddin Al-Helmy (left)

became a Parti Islam Se-Malaya (PAS) member on December 14, 1956 and

became party’s president on December 25, 1956. He was approached by some

PAS leaders like Haji Hassan Adli and others who guaranteed that the

leadership of PAS will be trusted to him. Under the leadership of Dr

Burhanuddin, the popularity of the party became famous and it became

more widely accepted by the Malays. In 1956 and 1959, the seat of

presidency was being contested and Zulkifli whom opposed him in the

presidency post. No doubt that Dr Burhanuddin’s personality, appearance

and attitude had won the hearts of many PAS members and thus elected him

as the new president of PAS. Ishak

Haji Muhammad or better known as Pak Sako was a prominent writer during

the 1930s and 1950s. A hardcore nationalist, his involvement began

before independence and continued thereafter. He fought for the idea of

the unification of Melayu Raya where Indonesia, Malaysia and Brunei are

united in one collective.

Ishak

Haji Muhammad or better known as Pak Sako was a prominent writer during

the 1930s and 1950s. A hardcore nationalist, his involvement began

before independence and continued thereafter. He fought for the idea of

the unification of Melayu Raya where Indonesia, Malaysia and Brunei are

united in one collective.The moniker "Pak Sako" came from 'Isako-san', which was the phonetic pronunciation of his name in the Japanese tongue. Ishak's other pseudonyms include "Anwar", "Hantu Raya" (The Great Ghost), "Isako San" and "Pandir Moden" (The Modern-day Pandir).

Pak Sako was the first with the idea to publish the Utusan Melayu (The Malay Post) newspaper and subsequently became the founder of the publication. He left Warta Malaya (Malayan Times) and travelled to Pahang, Kelantan and Terengganu to campaign for the establishment of the Utusan Melayu Press. He worked at the paper under Abdul Rahim Kajai as editor. During the Japanese occupation of Malaya, North Borneo and Sarawak, he became the editor of Berita Malai (Malayan News).

After the Japanese occupation ended in 1945, the leftist Malay activists regrouped to organise various political movements, such as the Malay Nationalist Party (Partai Kebangsaan Melayu Malaya; PKMM) led by Burhanuddin al-Helmy, the Angkatan Pemuda Insaf (Awakened Youth Organization; API) led by Ahmad Boestamam and the Angkatan Wanita Sedar (Cohort of Awakened Women; AWAS) led by Shamsiah Fakeh. Boestamam was part of the PKMM and API delegation that participated in the Pan-Malayan Malay Congress in 1946.

In 1955, Boestamam regrouped his supporters to form Partai Ra’ayat (People’s Party; PR) soon after his release from detention camp by the British colonial government. The new party was inaugurated in November 11, 1955 embracing a nationalistic but leftist philosophy focusing on the poor. PR formed a coalition with the Labour Party of Malaya led by Pak Sako. This became known as the Malayan People’s Socialist Front (Sosialis Rakyat Malaya) or the Socialist Front (SF) and was officially formed on August 26, 1958.

However, with the onset of the Indonesia-Malaysia Confrontation in 1962, opposition to the new federation came to be seen as being pro-Indonesia and anti national. This caused significant rifts among the Opposition parties. Many party leaders were also arrested and incarcerated including Boestamam and Pak Sako under the Internal Security Act (ISA).

By

9pm, people were already trickling into Dataran Merdeka, only to find

the historic field and nearby roads cordoned off, with a sign that

reads, “this area is closed to all activities, by order of the mayor of

Kuala Lumpur”.

By

9pm, people were already trickling into Dataran Merdeka, only to find

the historic field and nearby roads cordoned off, with a sign that

reads, “this area is closed to all activities, by order of the mayor of

Kuala Lumpur”. An hour later, with the crowd numbers at its peak, Maria, Samad (right),

and some Pakatan Rakyat leaders began to move towards a square outside

DBKL headquarters where Samad recited his ‘Janji Demokrasi’ poem.

An hour later, with the crowd numbers at its peak, Maria, Samad (right),

and some Pakatan Rakyat leaders began to move towards a square outside

DBKL headquarters where Samad recited his ‘Janji Demokrasi’ poem. Meanwhile, when met outside the LRT station, Samad said he was glad to see large crowds of youths.

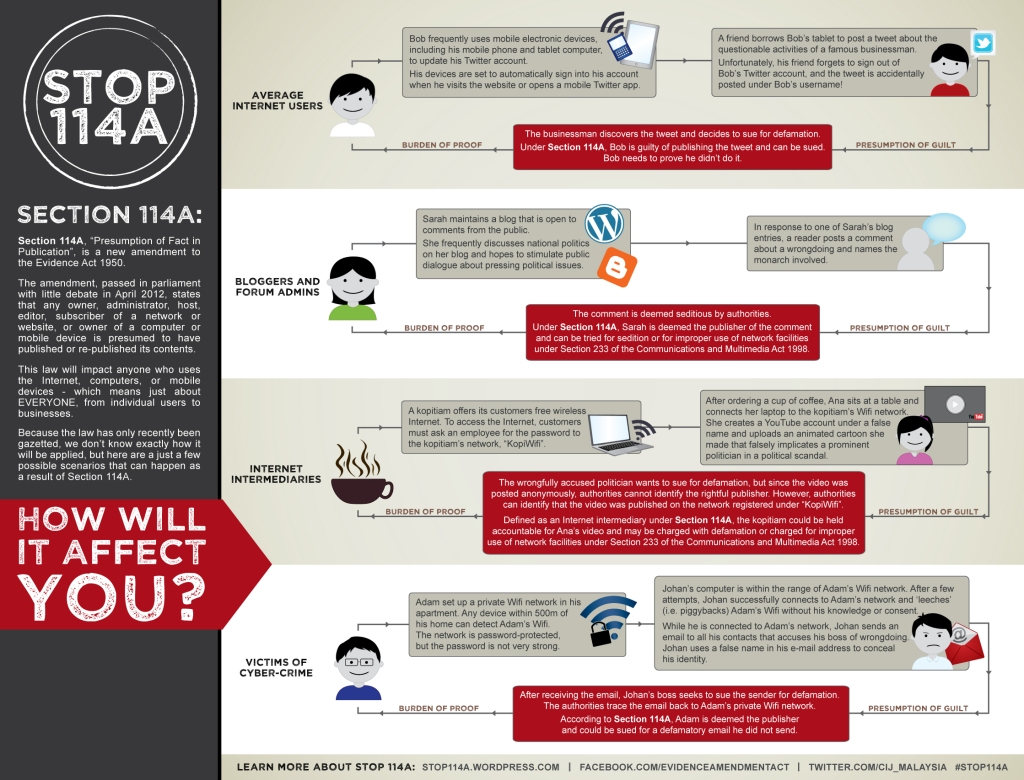

Meanwhile, when met outside the LRT station, Samad said he was glad to see large crowds of youths. About Section 114A

About Section 114A

"When

the terminal is completed, (it) must move. The present low-cost

terminal will be closed once KLIA 2 is opened," Bashir is quoted as

saying.

"When

the terminal is completed, (it) must move. The present low-cost

terminal will be closed once KLIA 2 is opened," Bashir is quoted as

saying. "These

cost overruns are matched by delays in the completion date from the

original 'up and running' date of September 2011 to the first, and

later, the second quarter of 2012.

"These

cost overruns are matched by delays in the completion date from the

original 'up and running' date of September 2011 to the first, and

later, the second quarter of 2012.