The anti-fake news bill must be withdrawn

COMMENT | The Malaysian Bar is deeply troubled by the introduction of the Anti-Fake News Bill 2018 in Parliament yesterday.

It is the stated intention of the government to have this legislation

passed in the current sitting of Parliament, and it will likely be

brought into force before the campaign period for the 14th general

election.

The drafting of the proposed legislation raises many questions

regarding its content, intent and impact. The Malaysian Bar highlights

the following:

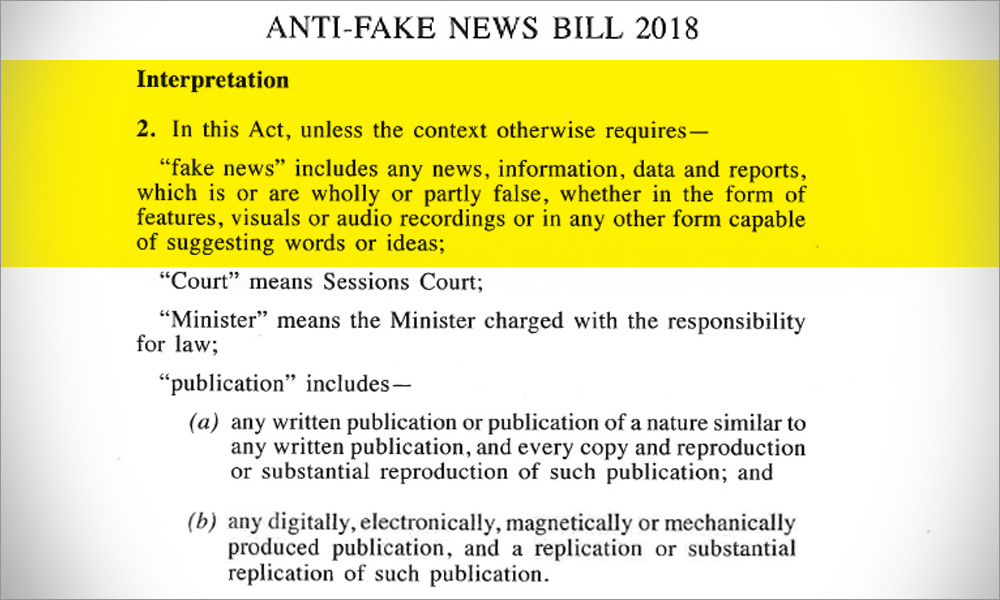

The definition of “fake news” does not simply include news but also

information, data and reports, which in its broadest sense exists “in

any…form capable of suggesting words or ideas,” that is/are “wholly or

partly false.”

'Fake' undefined

What is ‘false’ is not defined. “False news” is already criminalised

under section 8A of the Printing Presses and Publications Act 1984

(PPPA). The definition of “publication” in the PPPA is not dissimilar to

the various definitions in the proposed legislation.

A “false” communication is also criminalised under section 233(1)(a)

of the Communications and Multimedia Act 1998 (CMA). These provisions

beg the question of why there is any need to create a new law to

criminalise “fake” or “false” news.

The proposed law criminalises “fake news,” but since that is not

clearly defined, it could be used to suppress freedom of expression in

the context of expressing views or opinions.

The wording of the provisions is sufficiently wide for an action to

be brought challenging “correct” or “incorrect” views on, for example,

the economy, history, politics, science, and religion. Such a law may be

far too wide, and could be held to be ultra vires of the Federal Constitution.

The extra-territorial reach of the proposed legislation is, arguably,

wider than that of any other law in Malaysia. It will apply so long as

the “fake news concerns Malaysia or the person affected by the

commission of the offence is a Malaysian citizen.”

Therefore, neither the complainant nor the person complained of needs

to be physically present in Malaysia for the offence to have been

committed. Further, a court order to remove the publication can be

served “by electronic means,” which is not defined but could conceivably

include service by email, Twitter, WhatsApp, or other forms of text

messaging or social media.

An individual or entity affected by “fake news” can apply to the courts for an ex parte

order to remove the news, i.e., without informing the person being

complained of. There is no opportunity to have both parties present in

court to argue the veracity of the “fake news.”

The likely procedure is for the Sessions Court to evaluate the

complaint and any supporting evidence or documents submitted by the

complainant and, if the court decides that the item is “fake news,” to

grant an order.

An order can be challenged, but an application to challenge does not

operate to suspend or defer the original order, which must still be

complied with.

However, if it is the government that obtains the order, and it

alleges that the “fake news” is prejudicial or likely to be prejudicial

to public order or national security, and the court agrees, the order

cannot be challenged.

The proposed legislation does not deal with a situation if the

government publishes “fake news.” Looking at what is taking place around

the world, this is an omission that needs to be addressed.

If the offence is committed by a body corporate, the proposed law

allows for criminal liability to attach to its directors and officers,

but it can also attach to anyone “to any extent responsible for the

management of any of the affairs of the body corporate or was assisting

in such management.”

Thus, for example, if a news reporter writes a story about Malaysia

that is held to contain “fake news,” the editor or subeditor of the

company employing the news reporter would also be criminally liable.

Failure to abide by a court order leads to the commission of a

criminal offence, which carries a fine of up to RM100,000 and a

continuing fine of RM3,000 for each day of non-compliance. Such failure

also results in a contempt of court, and arrest is allowed under the

Criminal Procedure Code.

Why is new legislation necessary?

The many illustrations, in the proposed legislation, of how an

offence is committed under the proposed legislation actually involve the

issue of civil or criminal defamation, for which Malaysia has adequate

legislation and legal procedures.

This again raises the question of why new legislation is required. Of

serious concern is the fact that publishing a “caricature” can also

constitute an offence of “fake news.” Parodies and poking fun, which by

their very nature may involve some embellishment, would now constitute a

criminal offence.

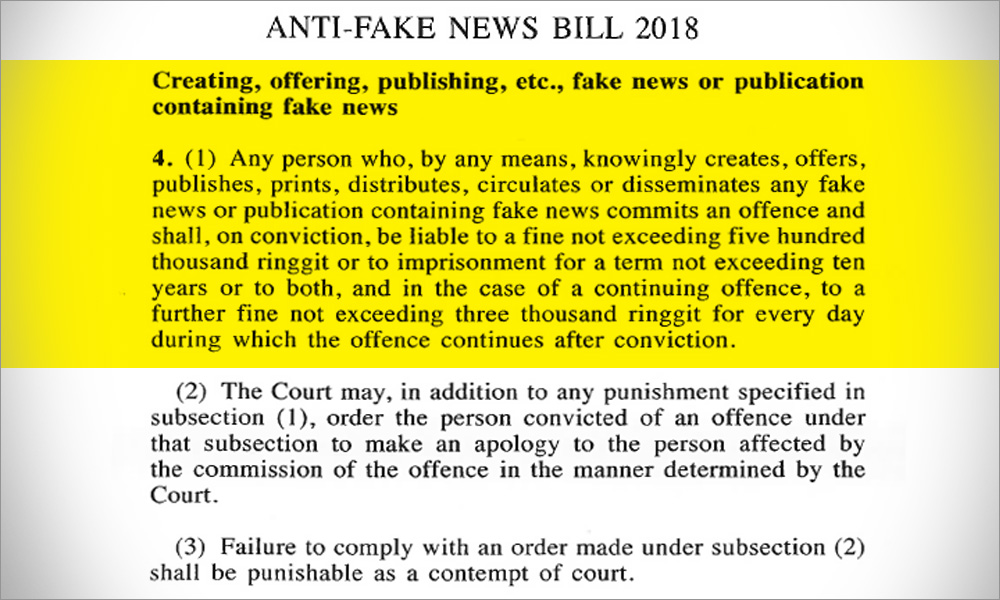

While the use of the word “knowingly” in the elements of the offence

denotes a requirement of intention, there is no requirement of malice or

ill intent, unlike section 8A of the PPPA. However, there is another

offence in the proposed legislation, of failing in one’s duty to remove

news, “knowing or having reasonable grounds to believe” that it is “fake

news.”

What constitutes “knowing or having reasonable grounds to believe” is

not defined. This lack of certainty gives cause for concern.

The real issue of “fake news,” which is what is currently in the

minds of many governments around the world, is about the setting up of

fake social media accounts and publishing news through it, of sending

tailored messages based on someone’s online profile, and the funding of

the same, and influencing outcomes of elections.

However, these matters are not adequately addressed in the proposed

legislation. Only the issue of funding is dealt with and criminalised in

the proposed section 5.

Again, other existing legislation already caters for the offence of

aiding and abetting the spreading of false news, so this provision does

not serve any purpose except for the provision of a huge maximum fine of

RM500,000 and/or a heavy maximum jail sentence of 10 years, to act as a

chilling deterrent.

Previous issues of the prime minister receiving a vast donation prior

to the last general election, and what may have been done with those

funds, have been wholly overlooked.

The presence in Malaysia of a foreign company involved in data analytics and online profiling is also ignored.

If the Malaysian government were genuinely concerned about the

possibility of foreign funding and foreign influence on the outcome of

our upcoming general election, surely it should have focused instead on

campaign finance reform, data security, and personal privacy.

Ultimately, the public is left to ponder the “value add” of this proposed new legislation.

Regrettably, the intended provisions enable:

- The Government to immediately silence “fake news”;

- Court orders to be rendered unchallengeable if there is accepted evidence of prejudicing public order or national security; and

- Intimidation of the media and honest practitioners of freedom of expression, who must now be 100 percent correct in their reporting, postings or statements, or else stand accused of being “partially false.”

Sensitivities about the reputation of Malaysia by way of negative

comments and criticisms can now be attacked through an extremely wide

extra-territorial application of the proposed legislation, putting this

in the same category as international terrorism, cross-border

corruption, money-laundering, and trafficking in persons.

While this issue should not be ignored, the proposed broad-based law

to criminalise the dissemination of news amounts to legislative

overkill.

The Malaysian Bar calls on the government to withdraw the proposed

legislation from consideration at this current sitting of Parliament,

and to convene a proper select committee to look comprehensively and

publicly into the issue.

The government must not legislate in haste.

GEORGE VARUGHESE is president of the Malaysian Bar.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.

Source:- Malaysiakini, 27/3/2018

No comments:

Post a Comment