Part 3 of 4 parts

The state of the labour movement in Malaysia (Part 1)

The origins of the labour movement in M’sia (Part 2 of a series)

How the British suppressed the Malayan labour movement (Part 3)

The last breath of the labour movement?(Part 4)

How the British suppressed the Malayan labour movement

This is part three of a series on the Malaysian labour movement.

FEATURE | In 1947, the

Pan-Malayan General Labour Union, which was established in 1946, changed

its name to Pan-Malayan Federation of Trade Unions (PMFTU).

It boasted a membership of 263,598, and this represented more than

half the total workforce in Malaya. 85 percent of all existing unions in

Malaya were part of the PMFTU.

The attitude of the Malayan worker was more assertive during this

period. For instance, a strike was reported of Chinese and Indian

hospital workers because they no longer wanted to be addressed as 'boy',

and workers began to see their subjection to physical punishments as

unacceptable.

Tamil trade unionists refused to suffer any longer the use of the

derogatory term “Kling”. Estate workers no longer dismounted from their

bicycles when a dorai, or planter, passed by.

In short, unions concern went beyond limited industrial relations

matters or employee-employer matters concerning work rights and working

conditions.

The British colonial government wanted to crush this development, and

the ever-strengthening labour movement decided to “reconstruct” the

organised labour movement in Malaysia and Singapore.

While the Singapore Trade Union Adviser, SP Garett, allowed the

Singapore GLU (SGLU) to re-organize as a federation and operate legally

without registering which led to the formation of the Singapore

Federation of Trade Unions (SFTU) in August 1946.

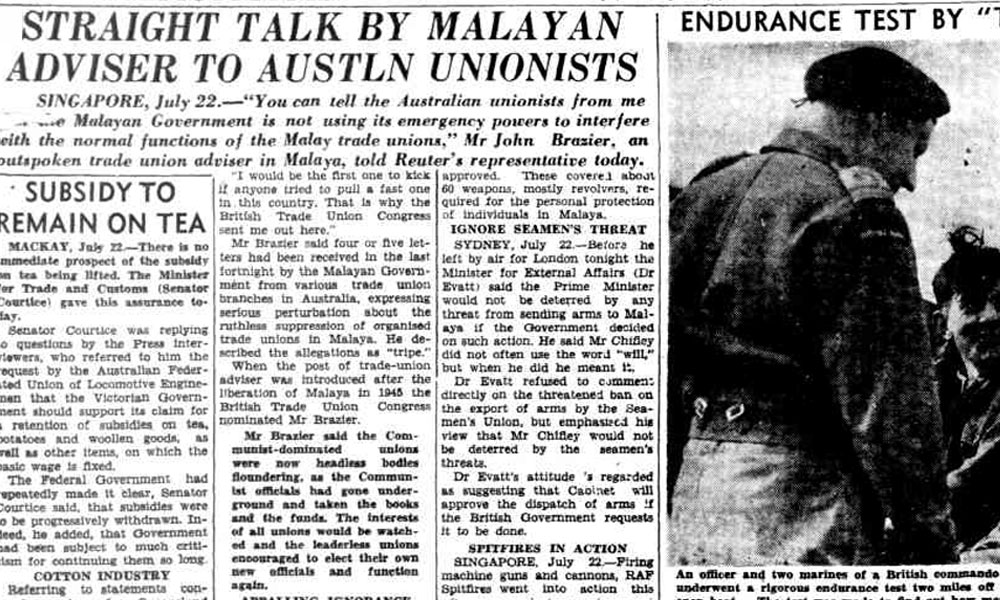

In Malaya, however, the then Trade Union Adviser John Alfred Brazier

did not want the same for Malaya – he did not want the PMGLU to be

recognised or continue to exist.

Brazier ruled that all the branch unions had to register, and that

thereafter there be no relationship between any of the newly registered

unions with the PMGLU (that later came to be known as the PMFTU). The

registered unions were not allowed to seek guidance or remit funds to

PMFTU. This created problems for the PMFTU, that ultimately led to its

demise.

The Trade Union Ordinance required the registration (or

re-registration) of trade unions according to sector or industry, and

this allowed the government to deny registration to unions they

considered strong, unacceptable or “militant unions”.

Until the proclamation by the British colonial authorities of a state

of emergency in Malaya and Singapore in 1948, most of the plantation

trade unions and federations of plantation trade unions in Malaya were

affiliated with the PMFTU.

It is of interest that the British may have considered the PMFTU a

bigger threat than even the Communist Party of Malaya (CPM), for the

PMFTU was outlawed even before the CPM was.

The influence of the Trade Union Adviser

Another method that was employed by the British, was to try and

influence the trade unions, and to this end in 1945, a British trade

unionist, John Alfred Brazier, was appointed by the government as Trade

Union Adviser.

English-educated middle-class individuals were groomed and trained to

replace the then existing progressive worker leadership of trade

unions. One of the targeted unions were the plantation worker unions.

The government-appointed trade union adviser’s objective was not to

strengthen, but rather, to weaken the labour movement in Malaya. This

included eliminating the labour movement’s role in the political,

socio-economic and cultural lives of the nation, and narrowly

restricting its activities to “industrial relations”, that is the

disputes between employers and workers.

This was an unnatural development, as workers are also citizens and

humans who live in the country. Who wins the federal, state and local

government elections is material – the wrong people and parties may mean

anti-worker and anti-trade union policies and laws.

This restriction led to further erosion of worker rights and the

power of negotiation for better terms. If the price of water, basic

amenities, and the cost of living go up, it also has a direct impact on

the lives of workers and their families. To bar unions and workers from

taking up or speaking on such issues was absurd.

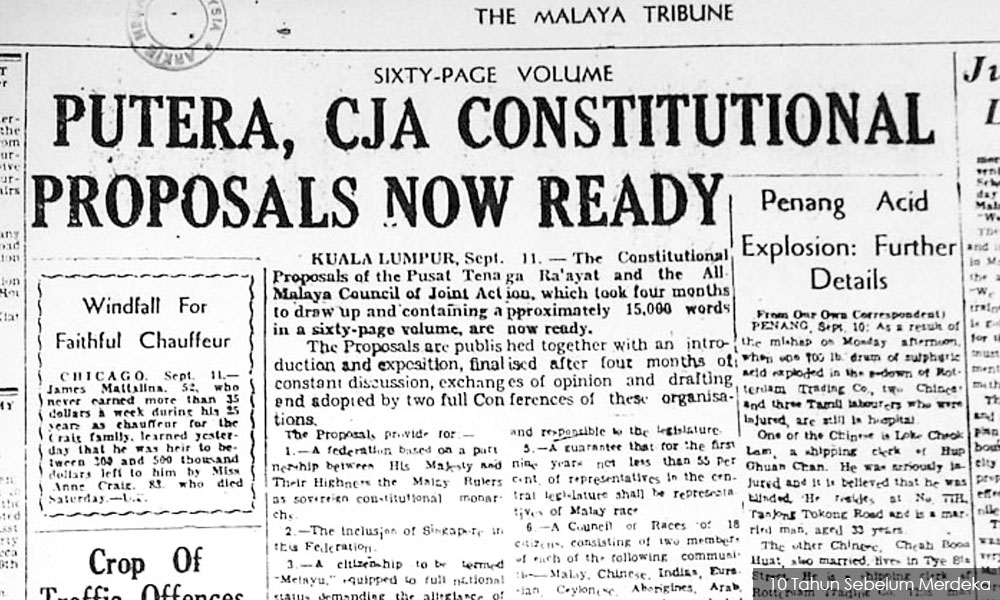

It must not be forgotten that workers and their unions had played a

very significant role in the struggle for independence of Malaya from

the British colonial government. They also played a significant role in

developing the Constitution of Malaya - now Malaysia.

The PMFTU, Clerical Unions of Penang, Malacca, Selangor and Perak,

and the Peasant's Union were a part of the All-Malayan Council of Joint

Action (AMCJA), with Tan Cheng Lock as chairperson and

Gerald de Cruz as Secretary-General, who actively campaigned on matters

concerning the Malaysian Constitution.

It must be reiterated that what the British did to the trade unions

in Malaysia was contrary to the accepted position and role of trade

unions in England. To this day, trade unions in the United Kingdom

continue to play an active role in the political life until today, being

still very much affiliated to the Labour Party.

The manner in which the British treated the labour movement in Malaya

and Singapore was not at all the same the way they treated their own

labour movement in Britain.

In Malaysia, the object was clearly “union busting” for the benefit

of employers and businesses, most of which were British-owned or

controlled.

Other laws to suppress labour movement

Besides the new labour laws, the British colonial government also used other laws to suppress or carry out “union busting”.

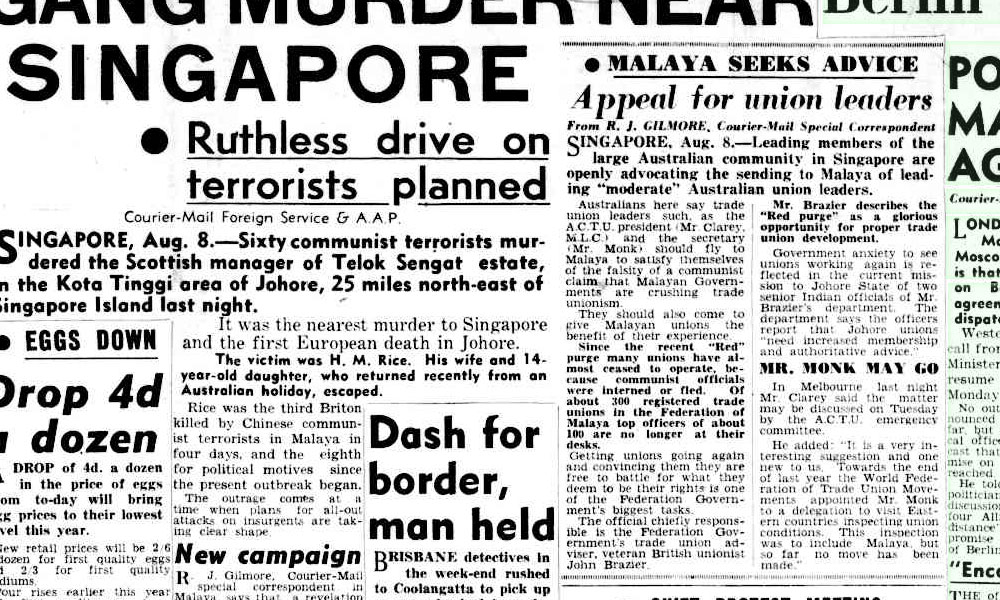

In 1947, the ordinary trespassing law was used to keep union organisers from meeting and speaking with workers in plantations.

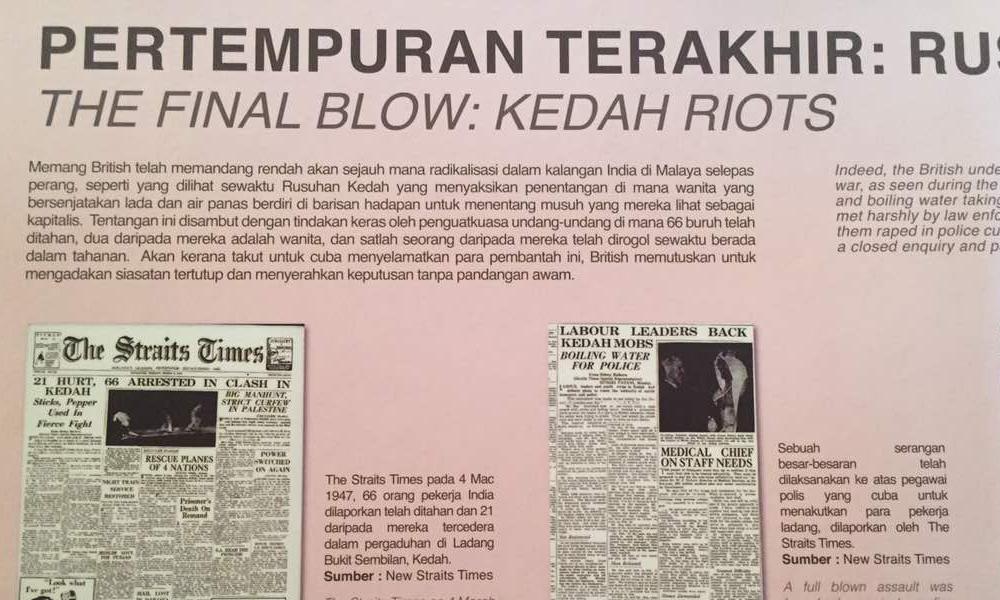

For instance in late March 1947, a large police force came to the

Dublin estate in Kedah to arrest a federation of trade unions official

for trespassing as he was speaking to a group of workers there. When the

workers closed ranks around the official, the police opened fire,

killing one worker and wounding five.

In a clash between police and workers at the Bedong estate on 3 March

1947, 21 workers were injured; whereby "the strike leader died of

injuries received at the hands of the police a few days later". 61 of

these workers were charged and sentenced to six months' imprisonment.

The existing law then was that workers could not be terminated just

for exercising their right to strike, which was a worker’s right. But in

October 1947, the Supreme Court ruled in a case involving three rubber

tappers that striking was a breach of contract and that the dismissal

was justified. This was a major change of law and policy.

Unionists were also convicted for intimidation. In November 1947, S

Appadurai, vice-president of the Penang Federation of Trade Unions and

chairperson of the Indian section of the Penang Harbour Labour

Association was charged for having written to an employer warning him

against using “backlegs”.

“Backlegs” are persons who act against the interests of a trade union

by continuing to work during a strike, or taking over a striker's job

during a strike. In law then and before this, it was wrong for employers

to use “backlegs” when workers are on strike. However, in this case,

the said union leader was found guilty and sent to prison.

In January 1948, K Vanivellu, secretary of the Kedah Federation of

Rubber Workers Unions was charged for having written to an employer

asking him to reinstate 14 workers who had been dismissed for striking

and suggesting that if he did not, the remaining workers might leave

their jobs.

Hence, various other laws and the courts were also used wrongly, for

the purpose of “union-busting” pursuant to the new British policy of

weakening the labour movement in Malaysia.

New amendments to the Trade Union Ordinance

The Trade Union Ordinance of 1940 was again amended to weaken unions.

New amendments to the Trade Union Ordinance were passed by the Federal

Legislative Council on 31 May 1948. The amendments were in three parts.

The first stipulated that a trade union official must have at least three years of experience in the industry concerned.

The second prohibited anyone convicted of certain criminal offenses

(notably intimidation and extortion, which were common charges against

unionists) from holding trade union office.

The third stated that a federation could only include workers from one trade or industry.

As Michael R Stenson said in his 1969 book, “Repression and Revolt:

the Origins of the 1948 Communist Insurrection in Malaya and Singapore”,

the first provision was seen as "a measure designed to exclude educated

'outsiders'”.

It also created problems because many workers worked in different

industries and sectors, as work available during that time was not

permanent, and had more of a seasonal or transient nature.

It was similar to what is happening now, with the use of precarious

short-term contracts, where after the end of contracts, workers have no

choice but to find another job, which more often than not is in a

different industry and sector.

The third part that insisted that a federation could only include

workers from one trade or industry effectively killed the PMFTU and even

the SFTU. This divided private sector workers further, and it also

affected public sector workers, because it prevented workers from

different sectors and industries from coming together and fighting for

better rights and common issues.

PMFTU outlawed in June 1948

On 12 June 1948, the British colonial government finally outlawed

PMFTU. This is interesting considering the fact that the Malayan

Communist Party and other left-wing groups were only made illegal later

in July 1948.

Can we say that for the British colonial government, the bigger

concern or threat was the labour movement and unions - not the Communist

party?

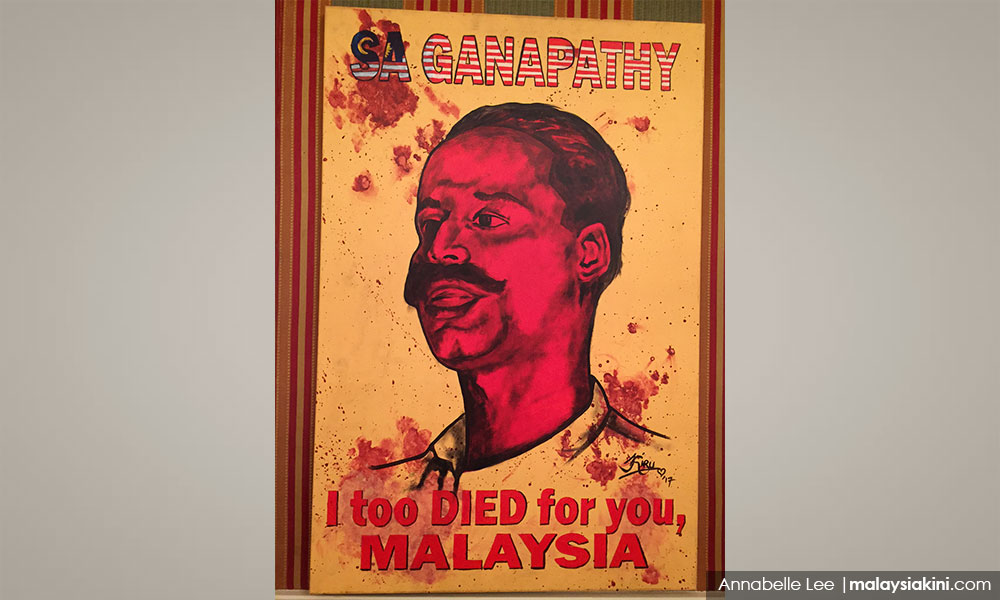

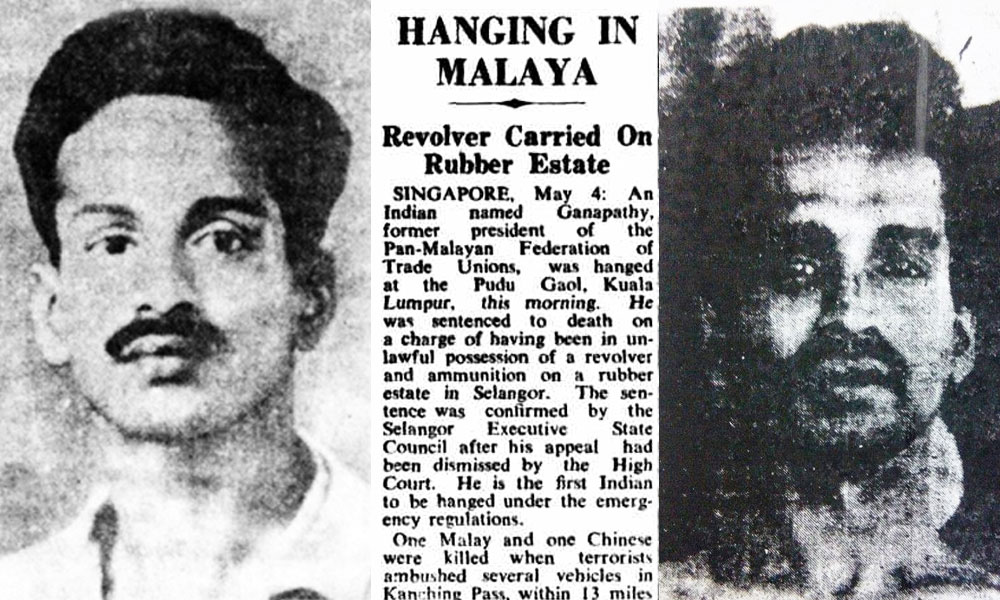

Many of the leaders of the labour movement were arrested, charged,

convicted and sentenced. SA Ganapathy, for example, who was the first

president of the 300,000-strong PMFTU, was hanged by the British in May

1949.

He was said to be on the way to the police to surrender a firearm he

found, when he was arrested by the

police and sentenced to hang in Pudu

Jail.

The birth of the Malaysian Trade Union Congress (MTUC)

Effectively, the British colonial government succeeded in crushing

the labour movement in Malaya. With the requirement of registration, and

the powers vested in the Registrar of Trade Unions, the government

could now eliminate the stronger “troublemaker” trade unionist and trade

unions, and break up the labour movement according to

sectors/industries – divide and rule.

In January 1949, there only remained 163 registered trade unions with

a total membership of only 68,814. In comparison, PMFTU had a

membership of about 263,598 – which represented more than 50 percent of

the total workforce.

The Council of Trade Unions was formed. It organised the Conference

of Malayan Trade Union Delegates from 27 to 28 February 1949, and this

gave birth to what is today known as the Malaysian Trades Union Congress

(MTUC).

Now, since the amended new trade union laws prohibited the formation

of trade union federations from different trades, sectors and industry,

MTUC could not be registered as a trade union or a federation of trade

unions, and had to be registered under the Societies Act as a society.

After Merdeka: The oppression continues

On 31st August 1957, Malaya got its independence from the

British, but alas, the position of the new Umno-led coalition government

that ruled since then until now did not differ much from their past

British colonial masters.

Malaysia may have gained independence, but workers and trade unions continued to be denied independence.

They continued to be oppressed and suppressed, by the Umno-led

government – who adopted and continued the British “divide and rule”

policy and laws, and the restrictions and control with regard to trade

union activities, trade union funds and even trade union leadership

restrictions.

The struggle for Malaysian independence took many forms ranging from

armed struggle to diplomatic negotiations, and for some the handing over

power to the Umno-led coalition was not real independence, and some

continued to struggle on.

The Umno-BN government and some leaders continue to be confused as to

whom we were fighting to gain our independence from – the British or

the Communist Party of Malaya (and others).

Members of the police and military serving the British colonial

government are shockingly still seen as “heroes of independence”, and

the recent invitation of 31 British army veterans to participate in the

2017 Independence Day celebration highlights this continued confusion.

Some suggest that the British choice in handing over power to the

Umno-led coalition, a “friend”, was basically to ensure the protection

of British-owned companies and assets, and the continued flow of

resources and profits from Malaysia to Britain.

All these may not matter, as we now accept that Malaysia is an

independent state. What matters is that workers, unions and the labour

movement continue to be oppressed and/or stifled even many years after

independence.

The role and influence of the labour movement in socio-economic and

political life and future of the nation continues to be slowly eroded as

the current government’s policy is perceived to be pro-businesses and

employers.

A greater concern seems to be to ensure smooth unhindered operation

of business and profits, something that may not change soon as the

government too now are employers in the growing number of

government-owned and/or controlled private businesses.

This article was first published by Aliran here. Malaysiakini has been authorised to republish it. - Malaysiakini, 18/11/2017

No comments:

Post a Comment